Bob Dylan, George Jackson, and the Endless Death of the `60s

(a Passion Play in 9 Acts)

“There was a fantastic universal sense that whatever we were doing was right, that we were winning… that sense of inevitable victory over the forces of Old and Evil… Our energy would simply prevail.” ~ Hunter S. Thompson, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, 1971

1. Not with a Whimper

Some decades end in their 9th year. Others stumble on, unwilling to give up the ghost. Dependent on whether you’re a glass half-full or half-empty kind of person, and given that you give a rosy red rat’s ass about it at all, you might argue it was Woodstock that signaled the end of the Sixties. Maybe it was Altamont. Maybe you feel the decade lingered on like a terminal cancer patient until the Fall of Saigon in 1975.

Or maybe the 1960s signed off on March 6 1970.

It’s close to noon when a rumbling begins on West 11th Street in Greenwich Village, followed by three explosions, the last strong enough to shatter windows up and down the street. Loud enough to be noticed a mile away at Bob Dylan’s apartment on Macdougal Street.

A brownstone townhouse — Number 18 — collapses. Two naked figures stumble out of the dust cloud and disappear into the 1970s.

Did Bob Dylan hear that explosion?

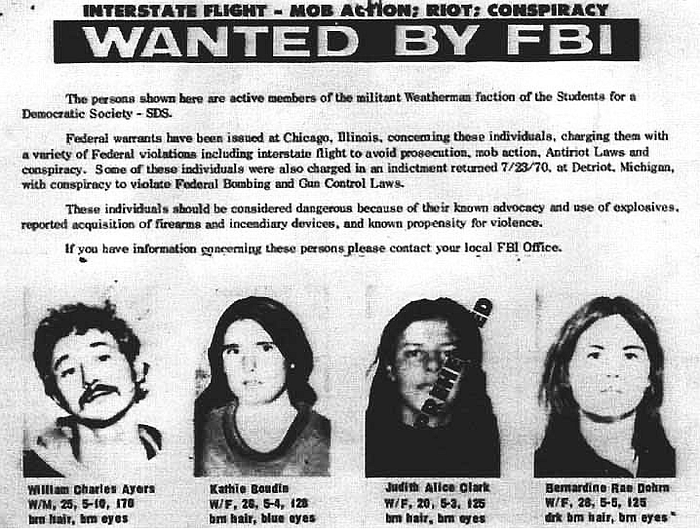

The group residing at the townhouse was the East Coast cell of “Weatherman,” a name consistently mislabeled in the mainstream media as “Weathermen” until the organization rebranded itself as the Weather Underground.

Of all the factions crawling from the wreckage of the Students for a Democratic Society in 1969 the Weather Underground was the most militant, stating in the manifesto which gave the group its name that the time for violent guerilla action against U.S. imperialism and racism was at hand. From 1969 into 1970, the Weather Underground claimed responsibility for 18 bombings of various capitalist and government properties.

The Greenwich Village townhouse explosion had been accidentally triggered by Weatherman Terry Robbins, the person who had suggested the line from “Subterranean Homesick Blues” as the title for the group’s manifesto. One of the devices Robbins was assembling went off, triggering a chain reaction of explosions that killed three of the five members of the Weatherman cell and obliterating the four-story townhouse.

Ultimately the explosion claimed the Weather Underground itself. The organization was finished by 1977, although its name still lives on with a weather information service.

2. The past is never dead. It’s not even past

By 1969 he was more than ready to be done with the Sixties, but the Sixties had sunk its teeth deep into Bob Dylan and wasn’t going to let go.

Plagued by obsessed fans showing up at his Woodstock door, walking on his roof, even screwing in his bed, Dylan moved from his Byrdcliffe home, HiLoHa, to a house on 39 acres of private land high up on Ohayo Mountain Road. The same year he bought an apartment in a 19th-century townhouse at 94 Macdougal Street, NYC, apparently hoping that Big City anonymity would shield him and his family when they came down from the country.

It could have worked out. The residents of 94 Macdougal and the surrounding buildings were professional working people, writers, people in advertising, music people who mostly gave Dylan, wife Sara, and the kids their own space when encountering them in the townhouse’s shared entrance or in the Macdougal-Sullivan private garden.

But then there was A.J. Weberman, who drove all the residents nutso by leading packs of feral fans anxious for a Dylan sighting to 94 Macdougal, who rang the entrance buzzer at all hours, and who regularly sifted through the building’s garbage barrels in the hopes of finding Dylan’s household detritus for Weberman analysis and unique interpretations.

“One night I went over D’s garbage just for old time’s sake and in an envelope separate from the rest of the trash there were five toothbrushes of various sizes and an unused tube of toothpaste wrapped in a plastic bag. ‘Tooth’ means ‘electric guitar’ in D’s symbology….”

In 1965, after taking LSD, A.J. Weberman had discovered “hidden meanings” in the songs on Dylan’s album “Bringing It All Back Home.” Those hidden meanings supposedly ranged from Dylan’s hopeless addiction to heroin to songs actually about, or addressed to, Weberman himself. According to A.J. many of those songs were a direct plea to Weberman to save “D” from himself and to help him get back to leading the revolution.

“I bet he really does a good job if he could find something to do, but it’s too bad it’s just my songs, ’cause I don’t know if there’s enough material in my songs to sustain someone who is really out to do a big job.”

By 1969, finding that Dylan was back in New York City, Weberman established the DLF — the “Dylan Liberation Front” — with the avowed purpose of re-radicalizing Bob Dylan, a monumental task given that there was little evidence that Dylan had ever been radicalized. But the DLF, largely comprised of students from Weberman’s Dylanology classes at the Free University of New York, held several protests in front of 94 Macdougal anyway, with the students calling for Dylan to “crawl out your window” and answer their charges that he had been co-opted by the Man.

Establishment tool that he was being made out to be, Dylan seemed surprisingly mellow about the harassment, generally ignoring Weberman and his DLF minions, with the strongest response coming from Sara who had taken to putting fresh dog poop in their trash bags before placing them outside. But it bugged Dylan enough that he called out the DLF group some 30-odd years later in “Chronicles” complaining they had, “paraded up and down chanting and shouting, demanding for me to come out and lead them somewhere — stop shirking my duties as the conscience of a generation.”

After two years and a DLF-staged street party for Dylan’s thirtieth birthday, which resulted in the NYPD shutting down both Macdougal and Bleecker streets, Bob Dylan had had enough already with the Dylanology. He tried reasoning with Weberman, he tried pleading in a series of phone calls where every other word was “man,” and Dylan sounding increasingly frustrated with this nutcase he’s been saddled with. He even tried co-opting Weberman, offering A.J. a gofer position if he disbanded the DLF and stopped scrounging through Dylan’s effing garbage, which was really pissing off the wife, man.

According to Weberman, he agreed to lay off, but the lure of the garbology branch of Dylanology proved too much. ”I went back to Macdougal Street, and Dylan’s wife comes out and starts screaming about me going through the garbage,” he related in an interview. “A few days later I’m on Elizabeth Street and someone jumps me, starts punching me.”

“I turn around and it’s like — Dylan. I’m thinking, ‘Can you believe this? I’m getting the crap beat out of me by Bob Dylan!’ I said, ‘Hey, man, how you doin’?’ But he keeps knocking my head against the sidewalk. He’s little, but he’s strong. He works out. I wouldn’t fight back, you know, because I knew I was wrong. He gets up, rips off my ‘Free Bob Dylan’ button and walks away. Never says a word.”

3. Enter Working Class Hero, Stage Far Left

After Dylan’s 1971 appearance at the Concert for Bangladesh, dressed as if he had just arrived from 1964 and singing the old acoustic songs, A.J. declared victory. He expressed satisfaction that he had brought the old Dylan back, and announced he was expanding his work to do the same for all rock royalty with the new Rock Liberation Front, “dedicated to exposing hip capitalist counterculture rip-offs and politicizing rock music and rock artists.”

“… I was actually hoping that John and Dylan would form a new band. I thought we could make musical history as well as political history. I thought it was going to revive the ’60s, that was my plan. This was at a time when the ’60s were ending but no one really wanted to admit they were ending and it was a time when the leaders were blaming themselves, like I was blaming myself. I was thinking, “If only I was a better leader, if only I was came up with more courageous or imaginative ideas.” ~ Jerry Rubin

During a protest at Capitol Records, Weberman announced that John Lennon and Yoko Ono had joined the new Liberation Front. Recently relocated to Greenwich Village, the radically reenergized Lennon had enjoyed hearing reports of Weberman hassling Dylan to get political, to the point where Lennon began wearing a “Free Dylan” pin himself.

Weberman would soon lose control of the RLF to Yippie activist Jerry Rubin, who had attached himself like a leech to Lennon since his arrival in America, and had already convinced Lennon and Yoko Ono to headline a US tour to disrupt and derail Nixon’s re-election campaign. Moreover, Rubin wanted Lennon’s help to get Bob Dylan on-board for the tour.

Between Dylan’s Bangladesh concert appearance and the surprise release of “George Jackson,” Dylan’s first politically-inspired song in years, anything seemed possible. But Rubin wanted Dylan to be cool with the RLF and its mission, and asked Lennon to co-sign an open letter published in the Village Voice demanding that Weberman apologize to Dylan for calling him a junkie as well as broadly hinting that now was the time for the Big D to saddle up and fight.

Weberman did issue a public apology, “for past untrue statements and also the harassment of Bob Dylan and his family,” but it was all for nada. The open letter accomplished nothing except to get the RLF put on the FBI’s watch list. Dylan didn’t respond, and Jerry Rubin’s dream of reviving the Sixties with a radicalized Lennon/Dylan superband faded back into the Twilight Zone.

An early investor in Apple Computer, Rubin became a multimillionaire in the late ’70s, moved away from radical politics and began working in the human potential movement and networking events for Wall Street professionals. He and his Yippie co-founder, Abbie Hoffman, also regularly debated each other on the college circuit in a format they titled “Yippie vs. Yuppie.” After being struck by a car and seriously injured, Rubin died of a heart attack in 1994.

The prolonged death of the Sixties would hit another milestone in 1980. On December 8, John Lennon was murdered at the hands of a crazed fan inspired by a novel from the 1950s, Catcher in the Rye, and its protagonist’s war against “phonies.”

“That radicalism was phony, really, because it was out of guilt. I’d always felt guilty that I made money, so I had to give it away or lose it. I don’t mean I was a hypocrite. When I believe, I believe right down to the roots. But being a chameleon, I became whoever I was with.” ~ John Lennon in a Newsweek interview

4. Huey Digs Bob Dylan

There were many people trying to recruit Dylan to the Cause, or at least their Cause, in the early ’70s. According to a lengthy profile in the New York Times by Anthony Scaduto, one of those causes was the Jewish Defense League. Scaduto reported Dylan attended several JDL meetings, met with its leader, Rabbi Meir Kahane, and donated money to the organization.

When questioned by Scaduto, Dylan shrugged off the story, saying that he had checked out the JDL to see what they were about: “In this day and age one can’t put one’s faith in organizations and groups just like that. There has to be a certain amount of comradeship, root beginnings and moral justifications to allow one to put his mind and body on the line.”

Mr. Jones: Does it matter to you when songs you’re writing now are being used as recruitment tools for militant street gangs, like the all-Negro faction in the United States?

Jude Quinn: Oh, yeah.

Jones: A group that promotes precisely the kind of violence your earlier songs oppose?

Jude Quinn: If you’re asking me, man, am I a member of the Black Panther Party, the answer’s no. ~ “I’m Not There”

In the same article, Scaduto repeats the story of a rumored meeting between Dylan and Black Panthers Huey Newton and David Hilliard. According to Scaduto, a Panther attorney had written to Dylan at Hilliard’s request, asking him to do a benefit or otherwise help raise funds for Panther trials. A more detailed account in Peter Doggett’s “There’s a Riot Going On,” says that Dylan responded by sending the Panthers a check for $40, a cryptic amount that Doggett speculates was a Dylanesque allusion to the average U.S. daily working wage in 1970.

Whether the Panthers understood they were being dissed or whether Dylan had actually sent a $40 check, the result was a face-to-face meeting of Dylan, Newton, and Hilliard which did not go well. Both Scaduto and Doggett report that Dylan began lecturing the two on the Panthers’ anti-Zionist stance. Hilliard called Dylan a pig and walked out. Newton brought Hilliard back but the meeting stalemated with Dylan adamant that he’d never support the BPP unless it changed its position on Israel.

Did the meeting even happen? Doggett is skeptical, and Dylan blew Scaduto off in his interview, claiming ignorance and telling Scaduto to go ask Huey about it. Newton was in China at the time and Hilliard in jail, so Scaduto wasn’t able to confirm the story with them, but several sources told him that they had heard it directly from Huey Newton.

This song Bobby Dylan was singing became a very big part of that whole publishing operation of the Black Panther paper. Bobby Dylan did society a big favor when he made that particular sound. If there’s any more he made that I don’t understand, I’ll just ask Huey P. Newton to interpret them for us and maybe we can get a hell of a lot more out of Brother Bobby Dylan. ~ Bobby Seale, “Seize The Time: The Story of the Black Panther Party”

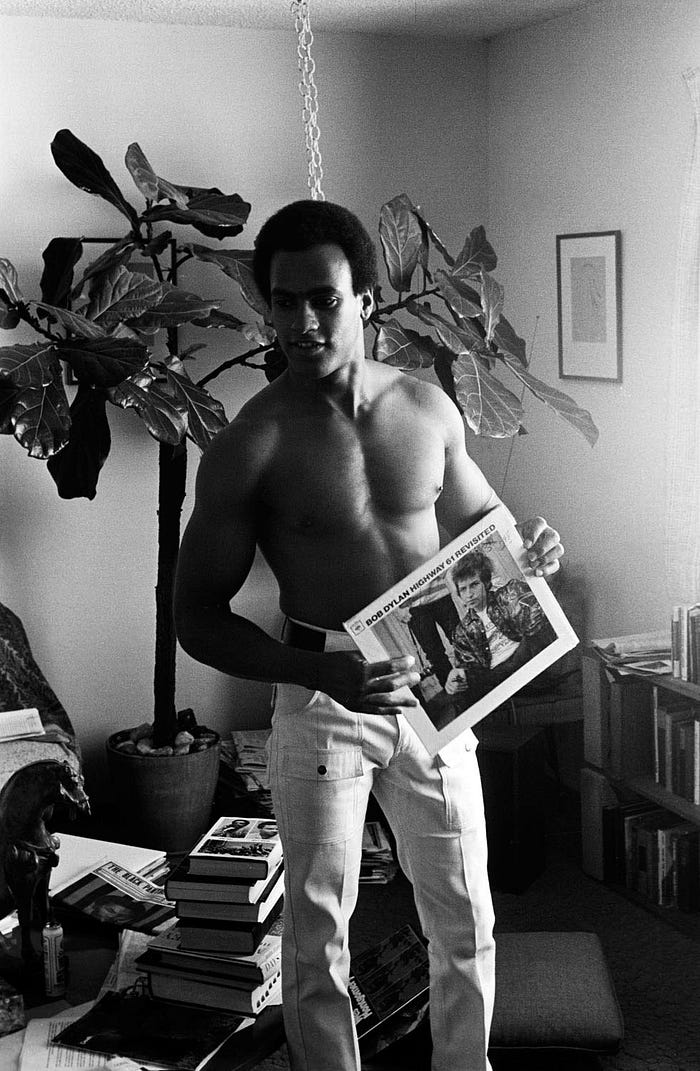

Huey Newton was a major-league fan of Dylan’s music, to the point where several Panthers — including David Hilliard and Bobby Seale — remembered his marathon playing of “Highway 61 Revisited” especially Dylan’s “Ballad of a Thin Man” as they put together issues of The Black Panther paper in the late ‘60s.

Newton could expound at length on “Thin Man” and its connection to racism and the Black experience. Newton’s interpretation of the song was detailed by Bobby Seale in his memoir and fictionalized in Todd Hayne’s “I’m Not There,” where actors playing Seale and Newton — wearing trademark Panther black sunglasses as they enjoy a spa massage — discuss the song’s meaning.

Bobby Seale: Well, I missed it. I missed it again. I missed it.

Huey Newton: Bobby, now you ain’t hearin’ me, man. No, we are the geeks. You dig?

Bobby: But then why is that cool?

Huey: No, man, we are the ones being paraded around like some sort of circus freaks. “Come on up and see Harlem, Mr. Jones, but make sure your window’s rolled up tight. “ This song is hell, man. You’ve got to understand, this song is saying a hell of a lot about society. All power to all people, man, that’s what it’s saying.

Bobby: I missed it again.

Huey: Bobby!

Bobby: Aw, Bobby nothing. Just play it again, Huey. Let’s play it one more time. ~ “I’m Not There”

After enduring years of harassment by the FBI’s COINTELPRO program the Black Panther Party was all but gone by the late ‘70s. The party was officially dissolved in 1982, although, like the Weather Underground, its name lives on. The “New” Black Panther Party, officially disavowed by the original, has been labeled a hate group by the Southern Poverty Law Center and the Anti-Defamation League due to its racist rhetoric and promotion of violence against Whites and Jews.

Huey P. Newton completed a PhD in Social Philosophy from the University of California, Santa Cruz in 1980, analyzing the government’s repression against the Black Panthers. He was murdered in 1989.

Newton’s widow, Fredrika, and David Hilliard co-founded the Dr. Huey P. Newton Foundation in 1995 to preserve Newton’s legacy and archival collection.

“The first lesson a revolutionary must learn is that he is a doomed man.”

~ Huey P. Newton

5. Troubled and I Don’t Know Why

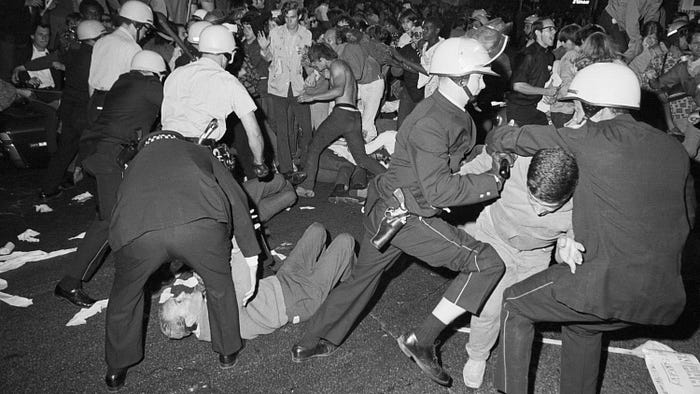

1968 and America is in shock. Narrowly escaping an assassination attempt in Los Angeles, Robert F. Kennedy comes to Chicago for the Democratic National Convention and electrifies the world when he joins the antiwar protesters in front of the Conrad Hilton hotel. During what would be known as “The Battle of Michigan Avenue” Bobby Kennedy himself is attacked by rioting members of the Chicago police, who push him through the hotel’s plate glass window and then continue to beat him as he lies sprawled on the broken glass.

All of this is captured on live TV as the protestors chant , “The whole world is watching.”

Still bloodied by the encounter , Kennedy holds a press conference later that night carried live by all three networks. “This is not America,” he says. “Our involvement in this war has to end. This country’s racism and discrimination and violence against its own citizens due to this foul war must end. We need to reclaim America’s soul before it’s too late for us all.”

Navigating a walk-out protest led by Chicago Mayor Richard Daley and a last-minute floor battle by diehard Hubert Humphrey supporters, the 1968 Democratic National Convention eventually nominates Robert F. Kennedy for President of the United States after Gene McCarthy throws his support behind Kennedy. McCarthy becomes the Vice Presidential nominee on the ticket.

“As for these deserters, malcontents, radicals, incendiaries, the civil and the uncivil disobedience among our young, SDS, PLP, Weatherman I and Weathermen II, the Revolutionary Action Movement, the Yippies, hippies, Yahoos, Black Panthers, lions and tigers alike — I would swap the whole damn zoo for a single platoon of the kind of young Americans I saw in Vietnam.” ~ Spiro T. Agnew, Missouri Republican Party Fundraising Dinner

Bob Dylan and Joan Baez have watched everything together — the protests, the riots, the attack on Kennedy, RFK’s impassioned speech, the nominations and acceptance speeches. And Dylan turns to Baez and says, “Y’know, I expect we need to do something.”

Having tried to shed the title for years, Dylan now doubles down on his unwanted role as the voice of the counterculture and “uncivil disobedience.” Instead of distancing himself from “finger-pointing,” Dylan begins producing new protest songs at hypersonic speed, including his first #1 single, 1968’s “Down on the Killing Floor,” backed by the equally powerful B-side, “The Ballad of Dean Johnson,” the story of the first casualty in the Chicago riots. Both songs will appear on Dylan’s new album “Crossroads.” In an unprecedented 15-page Rolling Stone review, Greil Marcus argues that all the album’s protagonists are at existential crossroads and grappling with choices that could lead to damnation or salvation.

The core of “Crossroads,” an expanded Delta Blues-soaked “Down on the Killing Floor,” is discovered to have has its title taken from a book about Black and White workers’ bitter struggle against the meatpacking industry in Chicago during the late ’30s, as Dylanologists writing in the Expecting Rain fanzine delight in pointing out.

After the release of the sardonic “Talkin’ Tricky Dick Blues,” Republican Presidential nominee Richard Nixon takes to calling Bob Dylan “the most dangerous terrorist in America” in his speeches and is accidentally caught on a hot mic saying, “that damn little Jew with his songs is the most dangerous white man in America. But I wouldn’t be surprised if he has a bit of the tarbrush in him too.”

In response to the Nixon leak the Black Panther Party issues a press release congratulating Dylan on being named a “Negro” by the Establishment with all attendant privileges such as “alienation, discrimination, and police intimidation.” Most news outlets won’t run the BPP story but the few that do also print Dylan’s reaction that “he’s felt like that his whole life.”

Nixon isn’t the only one thinking Bob Dylan is dangerous. At the direct orders of J. Edgar Hoover the FBI’s COINTELPRO (Counterintelligence Program) steps up its attacks against Dylan, continuing the propaganda campaign it had initiated in 1963 after Dylan’s controversial remarks about Lee Harvey Oswald at an event hosted by the Emergency Civil Liberties Committee.

The FBI disseminates a barrage of memos about Dylan to various federal agencies, including the Secret Service, suggesting Dylan is a potential national security threat. COINTELPRO also alerts its media contacts to Dylan’s connections to the Communist Party USA and Black Panthers and questions why anyone would honor “an individual of Dylan’s mentality.”

This leads to a nationally syndicated columnist publishing an attack piece linking Dylan to the Black Panthers, which reads as if the copy were taken directly from the FBI’s memos. In response, Dylan makes an appearance at a Harlem Cultural Festival “Summer of Soul” concert after announcing that he wouldn’t be performing at the Woodstock Festival, saying the latter event had “too much potential for too much nostalgia, too much kitschy sap, and too many drugs.”

On August 26, Dylan is introduced to the “Summer of Soul” audience by Black Panther Chairman, Huey P. Newton.

“I want to tell you about a song, it’s called “Ballad of a Thin Man,” Newton tells the audience. “This song is a very big part of the Black Panthers. Brother Bobby Seale digs the song. Brother Eldridge Cleaver digs the song. Brother George Jackson on Death Row digs this song. Sister Angela Davis digs this song. I know all the brothers in Attica dig this song. That’s because this song is all about the history of racism that has perpetuated itself in this world. There’s what’s called a ‘geek’ in this song, which is a carnival freak show with the worst… the shittiest job in the whole circus. He eats live chickens. He doesn’t want to but he does it to survive. And the people come to see him survive.”

“What the song is putting across is that it’s like those folks who put their family in a limousine and come down to take a tour of Harlem. You’ve all seen them on a Sunday, they’re the ones with the windows rolled right up and they come down to see the prostitutes and the ‘decaying community’. ‘They do this for pleasure or for a Sunday afternoon outing. But the prostitutes are there because they need to survive just like the geek, and the real freak show is those middle- and upper-class people who are down there because they enjoy it.”

“Bobby Dylan did all of us a big favor when he made that particular sound. It might be a little hard to dig at first, but listen to the words and listen to what the man has to say today. Here’s Brother Bobby Dylan.” ~ Huey P. Newton, “Summer of Soul” concert.

And Bob Dylan does walk on-stage, hugs Huey and without a word launches into a torrid soul-funk version of “Ballad of a Thin Man,” duetting with Nina Simone, who has appeared at his side and seems to have waited her entire career for this moment, to sing this one song with him.

The crowd first seems polite but unmoved, perhaps trying to process the song’s words as they were asked to do by Huey Newton. But when Dylan and Simone begin a cover of Sonny Boy Willamson’s “Don’t start me talkin’” people leap to their feet and begin shakin’ and moving.

In November Richard Nixon loses the 1968 presidential race to Bobby Kennedy after an overwhelmingly Black, Brown, and White youth turnout, In his Inaugural Address, President Robert F. Kennedy says that his first acts as president will be to immediately end America’s involvement with the war in Vietnam; shut down the FBI’s COINTELPRO program; and appoint a special commission to re-investigate the assassinations of Martin Luther King and his brother, as well as the attempt on his own life.

“There is more to these heinous crimes than the actions of faceless men with no apparent motive,” Kennedy says. “I tell you now that I will not rest until the full truth comes out, no matter where that leads, no matter who is found to be involved.”

Richard Nixon dies a few days later under mysterious circumstances at San Clemente. There are persistent rumors that Nixon’s death was either murder, deliberate suicide, or accidental autoerotic strangulation.

Three years later, a joint session of Congress and the President of the United States listen as the Senator from Massachusetts, Ted Kennedy, sets out evidence that Lyndon Baines Johnson had been directly involved with the assassination of John F. Kennedy.

Ted Kennedy concludes his speech by quoting Benjamin F. Butler, an earlier politician from Massachusetts and the lead prosecutor in the 1868 impeachment of Andrew Johnson:

“By murder most foul did he succeed to the presidency and is an elect of the assassin to that high office, and not of the people.”

And Joan Baez wakes in a New York hotel room.

6. Won’t You Listen to the Lambs, Bobby?

“I’ve chosen to preach about the war in Vietnam because I agree with Dante, that the hottest places in hell are reserved for those who in a period of moral crisis maintain their neutrality. There comes a time when silence becomes betrayal.” ~ Dr. Martin Luther King

Back in our sad reality, Joan Baez is trying to figure out whether she’s still in fantasyland or the real Manhattan of 1971. But as she fully wakes from her dream she reaches for the pad and pencil she always keeps by her bed and begins to write.

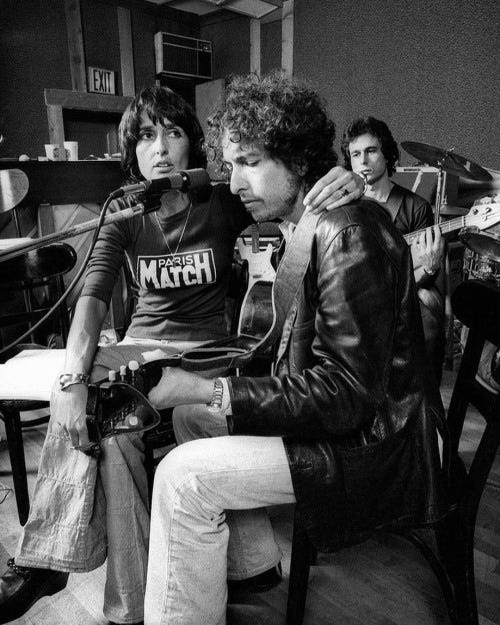

You have to wonder what was going through Joan Baez’s head as she drafted what would become “To Bobby,” a song still unfinished when she unveiled it that night in concert. Of all the people on the planet, she was one of a small group that could accurately predict what Bob Dylan’s reaction would be. Not his rationale, mind you. Not his feelings, for sure. But definitely, his reaction.

Did she really think think that playing a song on Dylan’s home turf, a song implying that he had betrayed the Movement like a shepherd abandoning his flock, a song that included the accusatory line, “Won’t you listen to the lambs, Bobby?” would produce anything good?

Perhaps because she did know him so well, perhaps she knew that somewhere deep inside was a part of Bobby Dylan who sympathized with the Movement and could still be swayed to action. Or maybe it was a last-ditch gesture of desperation. Like Jerry Rubin, Joan Baez knew the ‘60s were in its final days and the only option she had left was to try to recruit the one man who might turn things around.

“This is a song I’ve written for Bobby Dylan. I’d be ashamed to sing it to him, but I’ll sing it for you.”

Whatever her motivation, Baez played her first draft of “To Bobby” the night of September 27, 1971 in a benefit concert at Carnegie Hall that a reviewer from the Times sarcastically said had all “the ambiance of a garden party for the Panthers.” Anthony Scaduto was more sympathetic in his article, which took its title from Baez’s nascent song, writing that “To Bobby” received the longest ovation of the night.

“To Bobby” was received with dead silence at 94 Macdougal. But it hadn’t gone unnoticed by one of the brownstone’s occupants.

7. The Adjustment Center

A little more than a month before Baez’s performance of “To Bobby” George Jackson was killed by prison guards at San Quentin State Prison on August 21, 1971. Born the same year as Bob Dylan, Jackson died one month short of his 30th birthday.

At age 18, Jackson had been convicted of a gas station robbery of $70. Based on Jackson’s prior arrests and California’s draconian indeterminate sentencing laws, Jackson was sentenced to between one year and life in prison and shipped off to San Quentin. “The indeterminate sentence,” declared the judge, “would incentivize Jackson’s good behavior.”

Forcing him to bend the knee to regain his freedom or fight back and stay a prisoner forever did incentivize George Jackson, although not in the way the State wanted. While in San Quentin Jackson embraced radical politics and co-founded The Black Guerrilla Family, an in-prison revolutionary organization with the goals of promoting black power, maintaining prisoner dignity and overthrowing the United States government.

Temporarily transferred to Soledad Prison in 1969, Jackson and another prisoner, W. L. Nolen, established a chapter of the Black Panthers with Jackson later being named a Panther Field Marshal by Huey Newton. In January 1970 Nolen was killed by a prison guard, with a grand jury ruling that the guard had committed “justifiable homicide.” After another guard was found murdered, Jackson and two other Soledad prisoners were indicted, their alleged motive revenge for the killing of Nolen. If convicted the three will die in the California gas chamber.

“No Black person will ever believe that George Jackson died the way they tell us he did.” ~ James Baldwin

In August 1970, George Jackson’s seventeen year old brother, despairing that George would be murdered by the State if he remained in prison, burst into a courtroom with an assault rifle, took a judge and several bystanders hostage, and demanded that Jackson and the two other “Soledad Brothers” be released. After exiting the courthouse, Jonathan Jackson and the kidnappers attempted to flee with their hostages in tow. Police and San Quentin prison guards opened fire on the van Jackson was driving. At the end Jackson, two other convicts, and a hostage, Judge Haley, were dead.

George Jackson would publish “Soledad Brother: The Prison Letters of George Jackson” later that year, dedicating the book to Jonathan. And a year and fourteen days after his brother’s death, George Jackson himself was dead, on August 21, 1971, shot and killed by guards at San Quentin’s high-security “Adjustment Center.”

The dystopian “Adjustment Center” is where men sentenced to death go before they are moved to San Quentin’s death row. It’s also where the most violent inmates — as so deemed by the State — are held indefinitely. The Adjustment Center had been George Jackson’s intermittent home for 11 years.

Now he had finally been adjusted.

8. Tears in My Bed

While the resident of 94 Macdougal hadn’t publicly responded to Baez’s “To Bobby,” the song had definitely chafed him.

“Joan Baez recorded a protest song about me that was getting big play,” Dylan wrote in his 2004 memoir Chronicles, “challenging me to get with it — come out and take charge, lead the masses — be an advocate, lead the crusade. The song called out to me from the radio like a public service announcement.”

The complaint was the typical Dylanesque “Chronicles” blend of fact and fiction. “To Bobby” hardly got “big play” when it was released in 1972 as the B-side of a single and appeared on Baez’s album, “Come from the Shadows.” She dropped the song from her concerts after playing it a few times, and its doubtful that any radio station had “To Bobby” in heavy rotation, except maybe WLMB, “Listen to the Lambs.”

But “To Bobby” was a hit — a palpable hit — to its target. So, a few months after Joan Baez played at Carnegie Hall, Bob Dylan wrote an answer song.

It’s a pity that Bob Dylan didn’t started collaborating with Jacques Levy in 1971. The contradictory narratives around George Jackson’s death would have been perfect fodder for Levy’s theatrical bent.

“We can’t say who killed who. This was a careful plan to break out. It was a foolish plan.” ~ James Parks, associate warden, San Quentin Prison

Jackson may have been murdered or duped into an escape attempt with little chance of survival. He was set up by COINTELPRO… or the LAPD… or the CDCR… or some other alphabet agency. Or by rogue prison guards, the Black Guerrilla Family, the Black Liberation Army, or by the Black Panthers at the order of Huey Newton himself.

No one knows what led up to George Jackson’s death, although the stories surrounding it include disappearing and reappearing guns of various makes and calibers; an ill-fitting Afro wig; contraband nitroglycerine and plastique explosives that turned out to be neither; even a bizarre blackface, where a key visitor who attempted to see Jackson in prison on the day he died was said to have been replaced by a white impersonator.

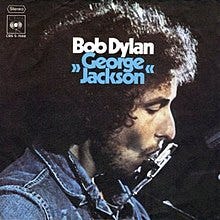

But it would be four more years before Bob Dylan would hook up with Jacques Levy. He turned to writing his first finger-pointin’ song in years in the way he knew best — fast and based on information gleaned from books and newspapers.

As Dylan mentioned several times on Theme Time Radio Hour, songs often act as cultural memes, especially among groups that don’t have other ways of distributing news. They’re often written quickly — days, sometimes even hours after an event, and the best ones spread like wildfire. Many are like a good news story: the date and place of the event, characters’ names, and quotations.

Dylan had probably read Jackson’s “Soledad Brother,” may have been given a copy by Howard Alk, who was sympathetic to the Black Panthers’ cause and had recently directed a documentary about the life and death of Fred Hampton, a leader of the Illinois Black Panther Party.

“Soledad Brother” would have given Dylan the basic information he needed for his song — the $70 robbery central to Jackson’s imprisonment; that Jackson “wouldn’t take shit from no one”; that the San Quentin prison guards were justifiably frightened of him.

The New York Times might have provided the rest in its coverage of Jackson’s death and its aftermath. The final paragraph of an article the Times published in September may have spawned Dylan’s last stanza for “George Jackson”: “Sometimes I think this whole world/ Is one big prison yard / Some of us are prisoners/ The rest of us are guards.”

“The idea that all black Americans are symbolically imprisoned is, of course, a cliché,” Mel Watkins wrote in the Times. “But it may be realistically said that prison is an exaggerated facsimile of society for those who suffer from racism, violence and bureaucratic insensitivity. That George Jackson’s last trick did not defeat his tormentors should then be no great consolation for America. There is probably something of Jackson in more Americans than most of us would like to consider.” ~ The Last Word: The Late George Jackson

Bob Dylan went into the studio on November 4, 1971 and recorded two versions of “George Jackson,” a “big band” cut with a group of musicians that became the A-side, and a B-side of Dylan performing on acoustic guitar. The single did relatively well, hitting #33 on the Billboard Hot 100 and remained on the charts for seven weeks. But it got little airplay except on the FM bands, as much from Dylan using the word “shit” as for its subject matter.

And that was that. “See Joanie,” he might have been saying . “I did what you asked and it didn’t make a damn bit of difference.”

“The dream is over. Now leave me alone.”

9. Helpless, helpless, helpless

A month before he recorded “George Jackson,” Dylan took wife Sara to see David Crosby and Graham Nash perform at Carnegie Hall. Dylan hated the crowd, “too much nostalgia, kitschy sap, and drugs,” he told his friend Tony Glover. “The whole house was like the Fillmore. I mean, this is Carnegie Hall and people are snorting coke in the aisles, everybody passing joints around… it was incredible.”

Dylan was also less than impressed with Crosby and Nash’s “cute” two-part harmonies and lost his shit altogether when Stephen Stills and Neil Young came on stage.

“They just sang this one song called ‘Helpless,” he complained to Glover. “And they just repeated this word over and over. ‘Helpless. Helpless. Helpless.’ And it really got to be a drag after a while, just hearing this word ‘Helpless.’ You just wanted to stand up and say, ‘What the fuck, man?’”

We were nice

Kids and cities and trees were nice

Everything…

I don’t know who we are anymore

And I’m starting not to careLook at us, Charley

Nothing’s the way that it was

I want it the way that it was

Help me stop remembering thenDon’t you remember?

It was good, it was really good

Help me out, Charley

Make it like it was ~ “Merrily We Roll Along, ‘Like it Was’”

Dylan and Sara decided to walk home after the show and came across a street vendor selling a variety of hippie paraphernalia. “We were walking down Seventh Avenue, and on the corner was this cat hawking bootleg records, just ‘Bootleg records, bootleg records, get ’em here.’ Just hawking ’em right on the street,” Dylan told Glover. “There was one he had of mine called ‘Zimmerman.’

It was a vinyl double album, a bootleg called “Zimmerman: Looking Back.” and included Dylan’s electric set at Royal Albert Hall in 1966. The music on the album is furious, direct, bitter. It’s perfect, like ice.

During that set the audience murmurs continuously like an angry sea, the sound roiling over the band’s endless tune-ups. The tension is so powerful that you can feel it even distanced through the recording. A round of rhythmic clapping is answered by Dylan mumbling into the microphone until the crowd quiets and he says, “ … and I just wish you wouldn’t’ clap so loud.”

“Ballad of a Thin Man” ends, greeted with not more than polite applause. A shout from the crowd. Laughter. Boos. Then a clear voice yells out, “Judas!”

More laughter. Something is tossed on stage. “Pick up your silver!” a voice calls. You can hear Robbie Robertson laugh. “Go ahead, pick it up,” he says. Dylan looks out into the sea of faces and plays a chord. “I don’t believe you,” he answers. And then, more strongly, as the other instruments come in, “You’re a liar!” He turns to the Hawks. “Get fucking loud,” he says furiously, and “Like a Rolling Stone” explodes.

The ’60s were over… but not for the last time.

In 1971 the Dylans turn back and confront the street vendor. “Gimme that,” Dylan growls and snatches the bootleg from the table. “Punk,” Sara hisses.

And the two walk away with their prize. The Seventies had begun.

Note

Writing something that mixes fact and fiction has its challenges, as Bob Dylan could tell us. It should go without saying, but I’ll say it anyway since this is the Interwebs, and somebody otherwise will complain that I made things up, that yes “Troubled and I Don’t Know Why” also known as “Joan Baez’s Dream” is pure fantasy. The section does includes some facts, but many are mix-mastered for dramatic purposes.

More importantly. as much as I could ensure, the facts/claims/quotes in the other sections are true or at least documented… but not necessarily happening at the time I say they happened.

To give one example Congressman elect Benjamin F. Butler was the lead prosecutor in the impeachment of Andrew Johnson in 1868, and did make the speech that I have my Teddy Kennedy quote. Incidentally, I think Butler’s speech was where Bob Dylan — student of the Civil War and Reconstruction that he is — picked up the title for his 2020 song.

And I think George Jackson was set up to die by someone — with the FBI and the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation being the most likely candidates. If you’re interested in the story of Jackson’s death, I recommend Jo Durden-Smith’s “Who Killed George Jackson?”

Could President Bobby Kennedy have shifted us off the path that led to our 2024? It’s nice to think so, but it’s unlikely that he would have even taken the Democratic nomination if he had lived. Given the iron grip that LBJ still had on the Party plus his white-hot hatred of the Kennedys, I think Johnson would have preferred to see the Democrats go down in flames — as it did in our reality— rather than see another Kennedy elected President.

Would Bob Dylan have made a difference if he had finally listened to the lambs and picked up the mantle he never wanted?

That you can decide for yourself. Hope you enjoyed.